If you have spent any time on this blog, you will know that one of the hobby horses that I get a lot of exercise on is the issue of people who own heritage sites and then destroy them. In Port Elizabeth, our bete-noir is Irish Slum lord Ken Denton, who, in the eyes of many, is like a one man plague when it comes to heritage destruction.

Sadly, we are not alone. Last week a real treasure in Johannesburg was demolished, in blatant defiance of an order to protect the site. It was done by the company Imperial Holdings, and I want to appeal to all of you who read this and care about this issue to express solidarity with the people of Johannesburg by boycotting this company. I will do some research during the week and let you know what companies and products are involved.

I have already lodged a protest with Imperial Holdings, and sent letters to friends,

MyPE chat forum and the local newspaper asking people to stand together and not allow this company to get away with such cynical and selfish actions. We need to send a strong message to all property developers that, no matter how big or rich they are, they cannot get away with robbing us of our heritage!

I received a fascinating newsletter today, written by Neil Fraser, and as he has put it all so eloquently, I am copying the letter here, rather than trying to rehash the facts.

"CITICHAT 3/2008

25 January 2008

Laundry Lamentations

At the end of the day what is it that makes some people care and others not give a damn? Why do some people thrill to experience examples of cultures and structures from a previous way of life whilst others see history and heritage as a stumbling block to their concept of progress? Why do we allow our lives to become so busy that in always focusing on the urgent, we forget about what is truly important?

Thousands of people a week must have driven past the Rand Steam Laundries buildings on the corner of Barry Hertzog Avenue and Napier Road without so much as a glance. With the actual laundry long since closed, some might have visited to do business with one of the small traders - blacksmiths, carpenters and furniture repairers - that operated from the site for the past 27 years. Few may have known the story behind the site and the buildings on it. Even fewer may have appreciated the sophistication of some aspects of the design and construction of the buildings to house what, in the early 1900s, was a new technology. Yet the complex encapsulated an amazing story that was part of the history of this crazy mining city. Now the buildings are gone, another example of man’s greed and of deliberate flouting the law of the land.

Charles van Onselen (“Studies in the Social and Economic History of the Witwatersrand 1886-1914 – ‘New Nineveh’) provides a fascinating history of the development of capitalism in Southern Africa. “The South African transition to capitalism – like that elsewhere - was fraught with contradictions and conflicts and its cities were thus capable of opening as well as closing economic avenues, and there certainly was always more than one route into or out of the working class”. One chapter that exemplifies this statement and provides amazing detail of this transition is that on the ‘AmaWasha’ – the Zulu washermen’s guild of the Witwatersrand.

The AmaWasha appeared to have emerged in the early 1870s in Natal through the lowly washermen’s caste of ‘Dhobis’ who had emigrated to Natal and started practicing their traditional profession – “the commercial washing of clothes”. Local Zulus were quick to recognise the opportunity to also earn an income from such work and even quicker to seize on the opportunity that the later discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand presented, accompanied as it was by rapid growth and services needs. By 1890, van Onselen records, there were already a couple of hundred AmaWasha, who had even adopted the ‘Dhobi’ turban, at work in the Braamfontein Spruit to the north of the mining camp. By 1896 there were over 1 200 washermen located at eight or more sites, the bulk of which appeared to have been concentrated in the Richmond area which was “by far the best developed of the sites….the owners provided eight wood and iron structures to accommodate some of the washermen and a small building in which the laundry could be safely stored overnight.” In October 1895, the washing sites were closed by health inspectors following a drought in that year that basically resulted in contamination of the work places. In 1896 a sub-committee of the Johannesburg Sanitary Board was, inevitably, appointed to examine longer-term solutions for public washing. As one would expect, the process provided an opportunity for capitalist connivance and corruption with vested interests trying to steer the process to their own interests even as far away as Witbank as well as to start mechanised processes in opposition to the labour intensive ‘AmaWasha’.

The first steam laundry was in fact founded before 1895/6 whilst the Auckland Park Steam Laundry Company was floated in June 1896 “with a registered capital of 12 500” (pounds Sterling). This was situated on the Richmond Estate, the centre of AmaWasha activities until they were forced to Witbank. There are still some rocks near the canalised stream on the site – the last exposed natural section of the Amawasha site.

The saga continued over a number of years; a return of some AmaWasha to the city, then their removal to Klipspruit, the growth of Chinese laundries and, of course, increasing technology. Of their removal to Klipspruit, van Onselen records that “the municipality was laying long-term plans to develop a permanently segregated community at Klipspruit” which would be both largely self-supporting bur possibly income generating. “The idea of segregation being paid for by the segregated held enormous appeal for white administrators. By 1906, an ironing room, a fenced in drying site and the first of one hundred specially designed concrete washtubs had been erected at Klipspruit. With blind ruthlessness and staggering cynicism the Council prepared to move the washermen for the last time – this time to an uneconomic washing site that shared its setting with the municipal sewerage works.”

History repeats itself! This time it is an aptly named corporation, Imperial, that‘with blind ruthlessness and staggering cynicism’ has destroyed not just one of the last local examples of steam driven industry, but crushed a place where South African history converged: the struggle of poor people to earn an honest living; colonial segregation; indifference; displacement; discrimination; lack of compassion and the eventual disintegration of the AmaWasha.

So how could this happen? After all we do have good legislation in the form of the National Heritage Resources Act of 1999, the Preamble to which contains, inter alia, these fine words: “This legislation aims to promote good management of the national estate, and to enable and encourage communities to nurture and conserve their legacy so that it may be bequeathed to future generations……our heritage is unique and precious and it cannot be renewed…..It helps us to define our cultural identity and therefore lies at the heart of our spiritual well-being and has the power to build our nation……it deepens our understanding of society…….”

Well, the story appears to be that the Imperial Group, through their property company, bought the site in March 2006 specifically for the construction of a showroom. The previous owners evidently warned them that this was a heritage site; the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust (PWHT), knowing the importance of the site and what it represented, applied for the site to be ‘provisionally’ protected in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act of 1999 and the Provincial Heritage Resources Agency of Gauteng (PHRAG) gave notice to that effect in the Provincial Gazette of 20 September 2006. PWHT also lodged an objection to any rezoning of the site for motor showroom purposes. A reporter who covered the purchase at the time was told by someone from Imperial that they weren’t interested in keeping the old buildings – they would demolish first and risk the fine, “It’s only R10 000.” The company’s attorneys denied that this comment had been made, stating that their clients were fully aware of the National Heritage Resources Act and that they had no intention of doing anything that would contravene the Act!

On Wednesday 9th of January this year preparations for demolition were underway, the roof sheeting was being stripped. PW&HT’s Flo Bird spoke to the responsible Imperial executive pointing out that they were acting illegally – he claimed that they had a demolition permit from the Chief Building Inspector of Johannesburg. Flo pointed out that the City does not outrank the Province in such matters and requested that the demolisher be instructed to stop work, which was done. Apparently the Johannesburg building inspector had issued a Dilapidation Notice, but he had warned Imperial that they needed a permit from the Heritage Authority (PHRAG) before they could proceed with demolition.

On Thursday 10th the demolition work started again, but this time with a difference. In Flo’s words “There was a mechanical grab smashing the buildings to pieces. Several large laundry buildings, two of the oldest on the site, already lay in small pieces. The grab hauled the masonry smashed it to the ground and then drove back and forwards crushing it. Any metal piece that survived that treatment was lifted in the air and crashed down until it crumpled. It was horrifying. Clearly the instruction was to destroy the buildings completely.”

At 3.30pm a stop order was delivered by PHRAG. At that stage there were still a number of heritage buildings left standing including the picturesque cottages at the corner of Napier and Barry Hertzog. Ignoring the stop orders from both PHRAG and the City, Imperial demolished the cottages on Sunday.

So what sanction can now be applied? I would think that there must be parts of the Companies Act that have been transgressed as well as all kinds of issues related to King 2 on Corporate Governance (can corporations take decisions that, knowingly, are against the law of the land for their own ends, as seems to be the case here?). But the main legislation would be the National Heritage Resources Act of 1999. Section 27(18) of the Act states ““no person may destroy, damage, deface, excavate, alter, remove from its original position, subdivide or change the planning status of any heritage site without a permit issued by the heritage authorities authority responsible for the protection of such site.”

Section 51 (1) (a) that any person who contravenes the above “is guilty of an offence and liable to a fine or imprisonment or both such fine and imprisonment as set out in Item 1 of the Schedule.” Item 1 of the Schedule states “a fine or imprisonment for a period not exceeding five years or to both such fine and imprisonment.” In a previous case, the fine was R300 000-00 with a five year suspended sentence!

However, the Act goes further – in terms of 51(8) a court may also order the guilty party to ‘put right’ the result of their actions or order the party “to pay a sum equivalent to the cost of making good” AND in terms of 51 (9) an order can be served on the party that no development should take place on the site for a period of ten years except for making good the damage and maintaining the cultural value of the place.

Seems to me that a seemingly deliberate and premeditated breaking of the law needs the whole book thrown at it. The previous heritage structures must be rebuilt and the story of Amawasha and the mining town they serviced must be told and portrayed so that “it may be bequeathed to future generations” – the cottages can once again house the craftshops and the site should be turned into an active place for the community. The story of the perfidy of Imperial and the punishment meted out to them in terms of legislation should also be encapsulated so that everyone becomes aware of the law and the consequences of arrogance in disregarding it. Anything less would be a travesty.

London has the Imperial War Museum, at least we could have the Imperial Rand Steam Laundry Museum!

Cheers, neil

PS. Want to help? I had this message from Flo Bird:

“Please support us in pressing for the perpretrators to be brought to justice, for the land to be frozen for development for 10 years and for the reinstatement of the heritage buildings on the Rand Steam Laundries site.

They were not marble palaces, but simple industrial buildings built of wood and iron, bricks and plaster. Even Imperial should be capable of rebuilding those.

Please go to our website:

http://www.parktownheritage.co.za/heritage.htm and press on the newsflash. If it doesn’t come up immediately you need to press the refresh button.

1. Please copy and paste the petition, filling in your name, and e-mail it back to us.

2. Please pass on to all people on your mailing list. "

(That bottom one had Max and I howling with laughter this morning!)

(That bottom one had Max and I howling with laughter this morning!)

The kitchen cabinets also got the beaded treatment, with custom made chilli handles.

The kitchen cabinets also got the beaded treatment, with custom made chilli handles.

And in the sitting room, the end wall was remodelled to unify the fireplace, TV cabinet and bookshelves. Woven baskets were made for the shelves, to hold all the little loose bits and pieces that tend to accumulate in such places.

And in the sitting room, the end wall was remodelled to unify the fireplace, TV cabinet and bookshelves. Woven baskets were made for the shelves, to hold all the little loose bits and pieces that tend to accumulate in such places. (As a matter of interest, here is a before pic showing the dated and unbalanced oak shelves, with huge ugly step below fireplace, and tv so far across to the right that it was impossible to view from a couch against the only long wall in the room.)

(As a matter of interest, here is a before pic showing the dated and unbalanced oak shelves, with huge ugly step below fireplace, and tv so far across to the right that it was impossible to view from a couch against the only long wall in the room.)

....with double shower heads next to it. The tile layout highlights the whole feature.

....with double shower heads next to it. The tile layout highlights the whole feature.

It was a lot of fun!

It was a lot of fun!

One of the things I really enjoy is trying out new restaurants. I love eating out, experiencing the atmosphere, enjoying the view if there is one, and people-watching if there isn't. If there is music thrown in, that's a bonus. Primarily, I love not having to cook!

One of the things I really enjoy is trying out new restaurants. I love eating out, experiencing the atmosphere, enjoying the view if there is one, and people-watching if there isn't. If there is music thrown in, that's a bonus. Primarily, I love not having to cook!

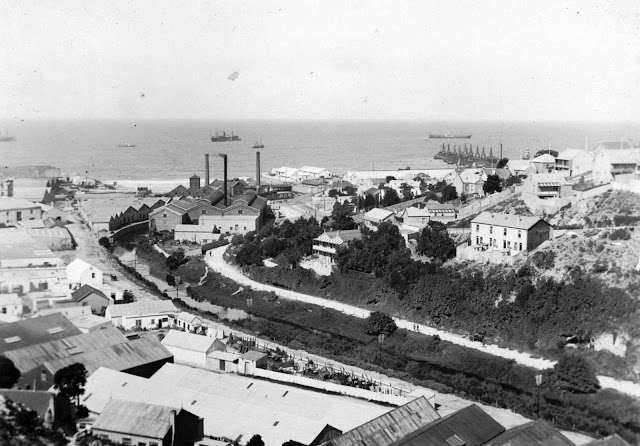

And here it is in the late 1800s after the river had been channeled into a canal, to the left of the building (Tramways is the one with the 3 belching chimneys!)

And here it is in the late 1800s after the river had been channeled into a canal, to the left of the building (Tramways is the one with the 3 belching chimneys!)

As recently as August 2006, the river flooded again, this torrent was the road leading past the Tramways Building, as you can see the street lights which are normally on the centre island are now in the river!

As recently as August 2006, the river flooded again, this torrent was the road leading past the Tramways Building, as you can see the street lights which are normally on the centre island are now in the river!

Given all this, it is good news to hear that a project is being considered, which will remove the canal, dam up the river to create a natural lake, and establish it with indigenous plants and waterlife to produce a balanced ecosystem. This will tend to absorb much of the impact of future floods, as well as creating a pleasant environment around the revamped building. Let's hope this plan gets off the ground soon. It is exciting to see that people are at last waking up and entertaining these visionary ideas, and actually beginning to implement some of them. Watch this space!!

Given all this, it is good news to hear that a project is being considered, which will remove the canal, dam up the river to create a natural lake, and establish it with indigenous plants and waterlife to produce a balanced ecosystem. This will tend to absorb much of the impact of future floods, as well as creating a pleasant environment around the revamped building. Let's hope this plan gets off the ground soon. It is exciting to see that people are at last waking up and entertaining these visionary ideas, and actually beginning to implement some of them. Watch this space!!